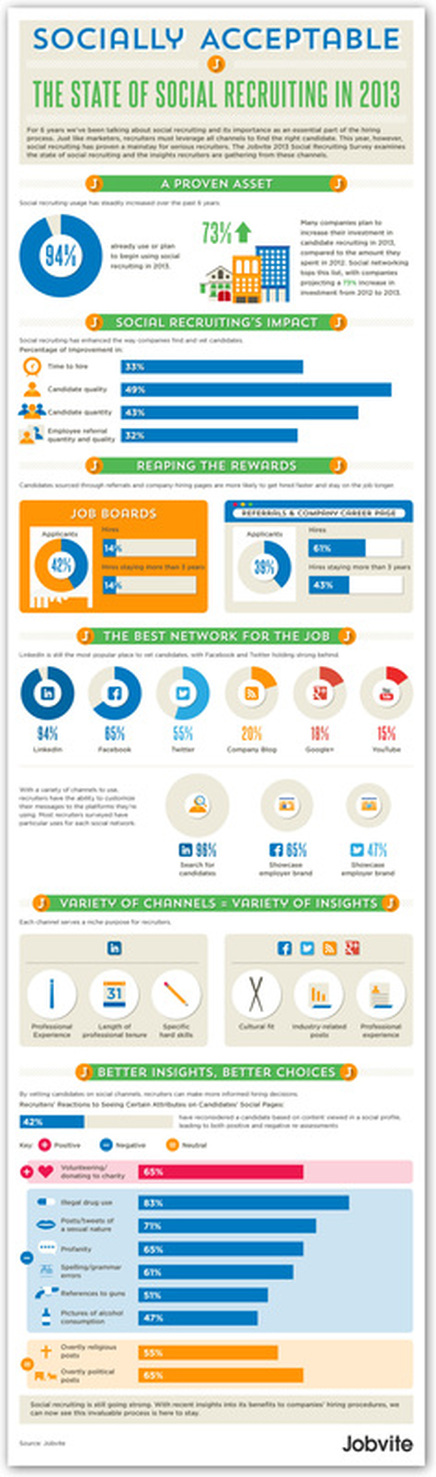

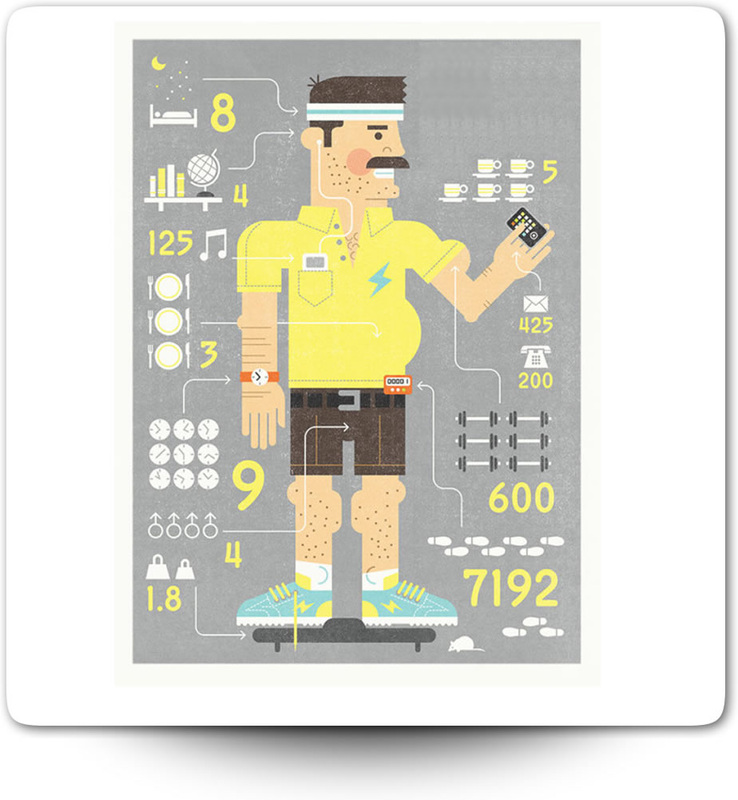

Job boards are so last decade. In 2013, one-click job applications are all the rage. Digital experts say it's becoming increasingly difficult to separate recruitment from social media in this day and age. Employers are extensively using online venues including LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter to broadcast available positions; in fact, it's become an essential part of most companies' current recruitment strategies. According to Jobvite's 2013 Social Recruitment Survey, 94 percent of the 1,500 respondents are already using social recruiting and plan to increase their investment in candidate recruitment by 73 percent. The reasons why so many organizations are eager to tap into social recruiting are pretty obvious: they spend less time to hire (by 33 percent) and see significant increases in candidate quality (43 percent), as well as in quantity (43 percent). When screening candidates on social networks, recruiters can also better assess the candidate quality and make more informed hiring decisions. Check out the findings of Jobvite's survey, illustrated in the infographic below: Read More: http://tinyurl.com/lahuawx

0 Comments

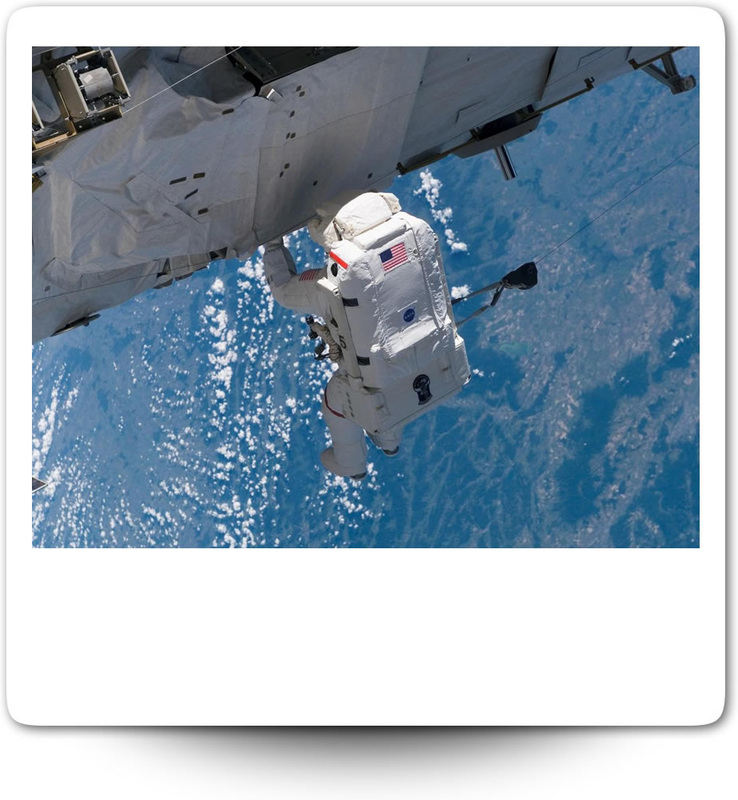

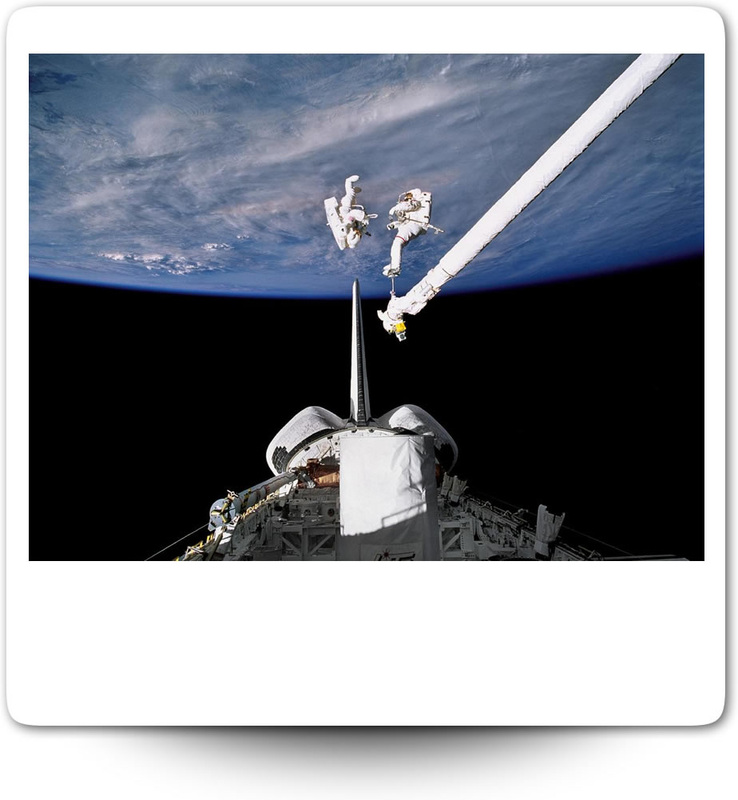

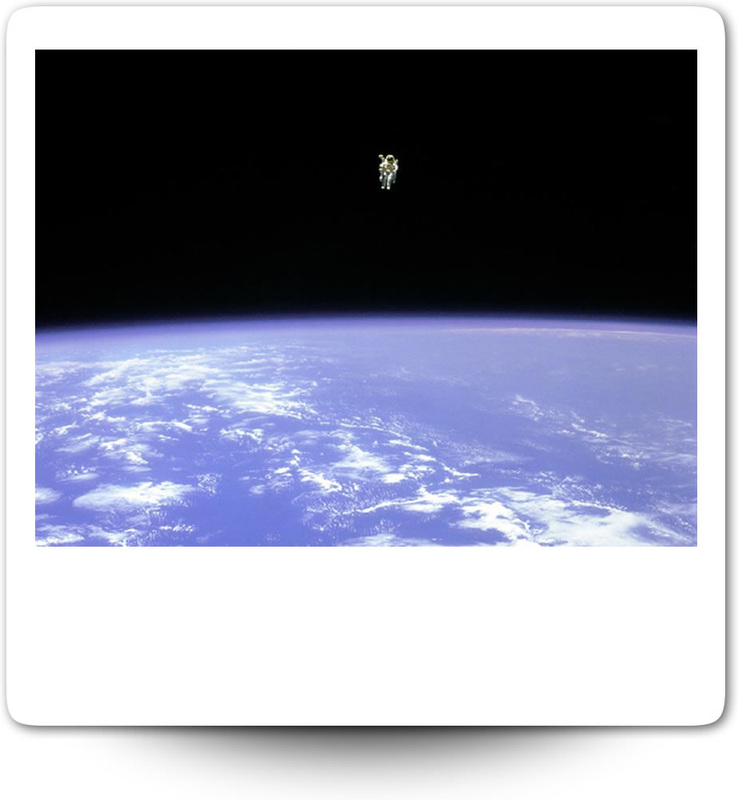

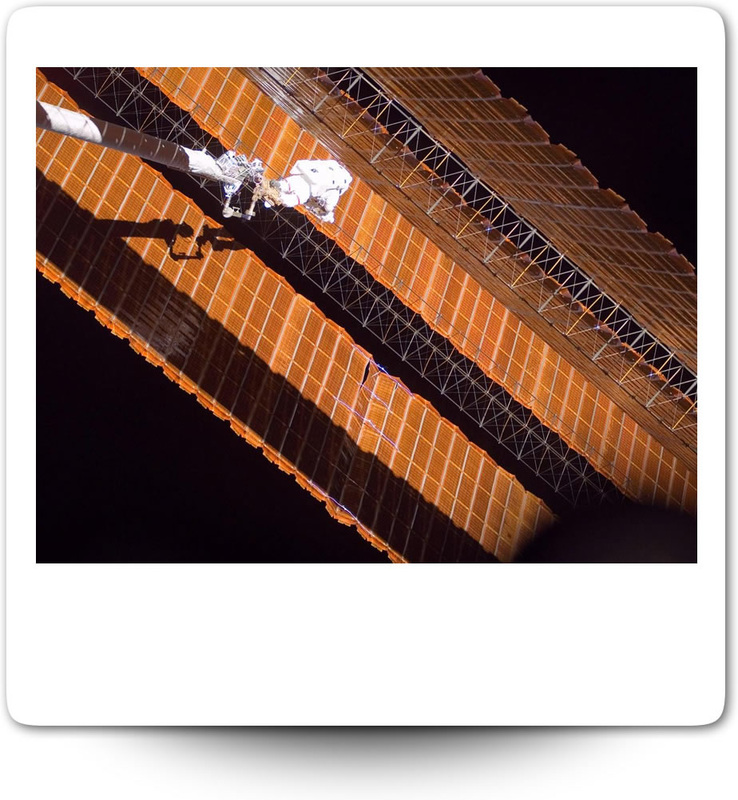

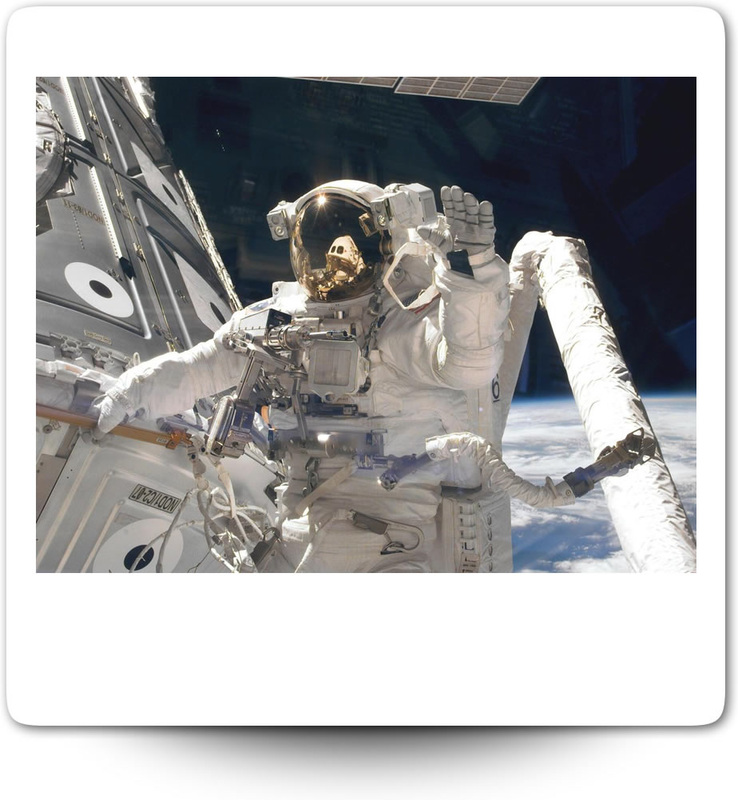

Some of the most iconic images from space are the ones that show astronauts floating outside the safety of a spacecraft. Week-End Reading: http://philippemora.tumblr.com

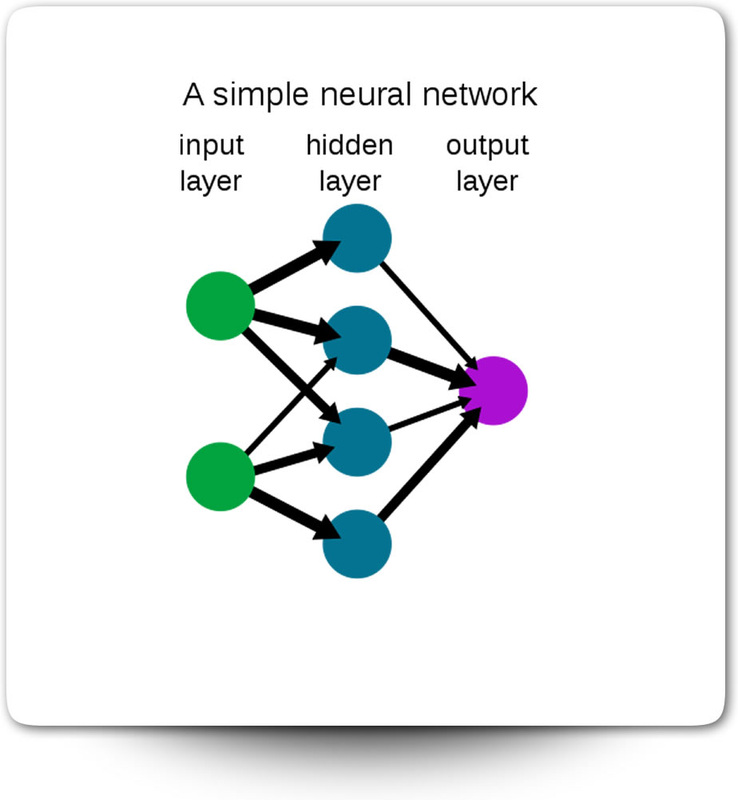

Facebook Launches Advanced AI Effort to Find Meaning in Your Posts

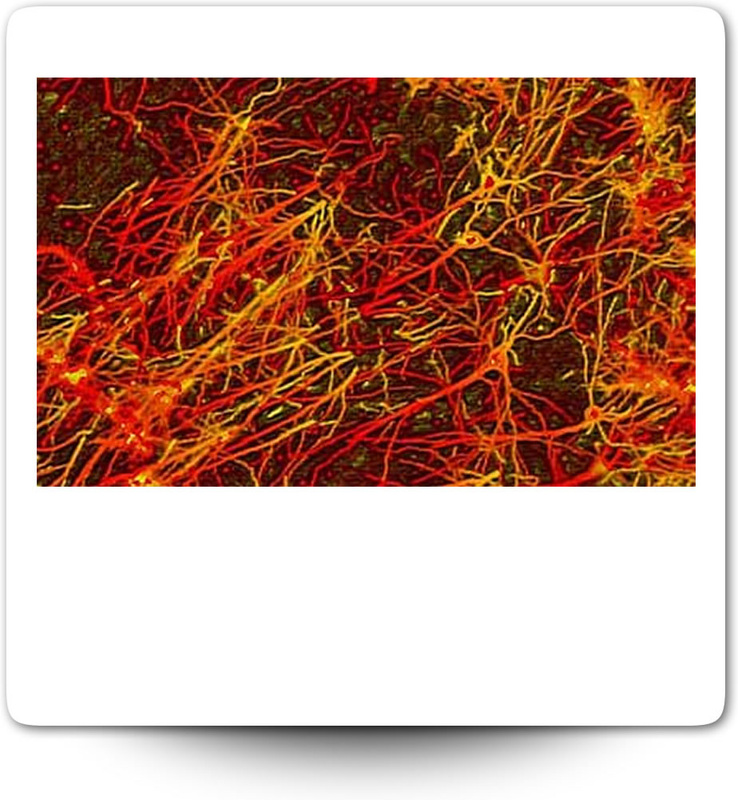

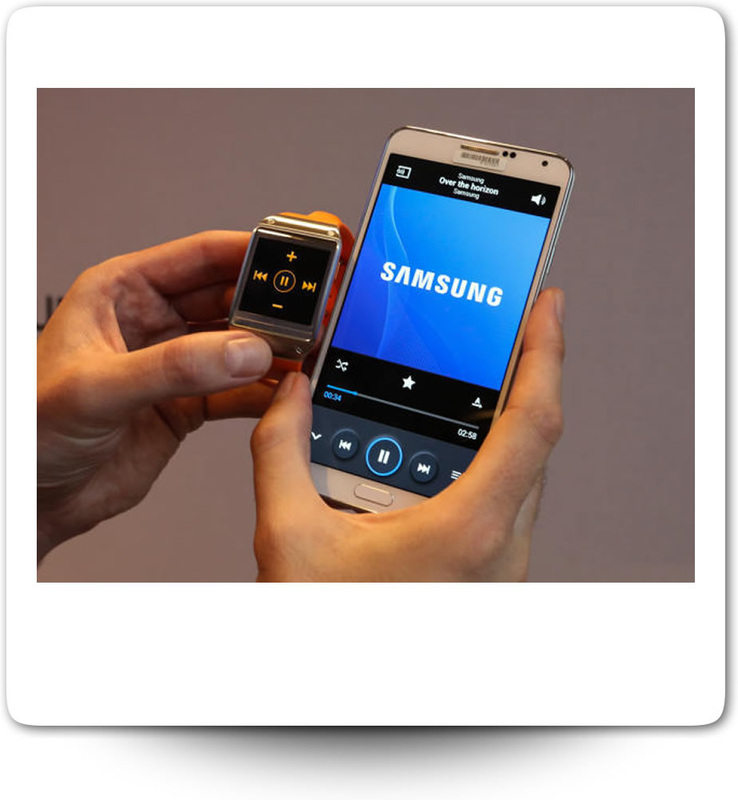

Facebook’s piles of data on people’s lives could allow it to push the boundaries of what can be done with the emerging AI technique known as deep learning. Deep learning could help Facebook understand its users and their data better. Deep Learning is a new area of Machine Learning research, which has been introduced with the objective of moving Machine Learning closer to one of its original goals: Artificial Intelligence. In fact, Deep learning is just a buzzword for neural nets, and neural nets are just a stack of matrix-vector multiplications, interleaved with some non-linearities. I’ve done some work in the 90s on multilayer neural networks for use in speech recognition, however at that time, the only processing power we had was a network of sparc stations grinding all night to recognize one number. I am very curious to see where Facebook immensely innovative teams (see The Graph and the OpenCompute Project) is going to take us this time ! -Philippe [Thank you MIT Technology Review | By Tom Simonite 09.20.13] Facebook is set to get an even better understanding of the 700 million people who use the social network to share details of their personal lives each day. A new research group within the company is working on an emerging and powerful approach to artificial intelligence known as deep learning, which uses simulated networks of brain cells to process data. Applying this method to data shared on Facebook could allow for novel features and perhaps boost the company’s ad targeting. Deep learning has shown potential as the basis for software that could work out the emotions or events described in text even if they aren’t explicitly referenced, recognize objects in photos, and make sophisticated predictions about people’s likely future behavior. The eight-person group, known internally as the AI team, only recently started work, and details of its experiments are still secret. But Facebook’s chief technology officer, Mike Schroepfer, will say that one obvious way to use deep learning is to improve the news feed, the personalized list of recent updates he calls Facebook’s “killer app.” The company already uses conventional machine learning techniques to prune the 1,500 updates that average Facebook users could possibly see down to 30 to 60 that are judged most likely to be important to them. Schroepfer says Facebook needs to get better at picking the best updates because its users are generating more data and using the social network in different ways. Samsung Galaxy Gear: the wearable space is still bringing all the old metaphors of computation and still interpreting them in a literal way—that they are a smaller smartphone, or a little computer. And that’s why Samsung is introducing half-baked, pre-”me too” devices with neither innovative value nor consumer demand, with only purpose is to pre-empt an apple move.

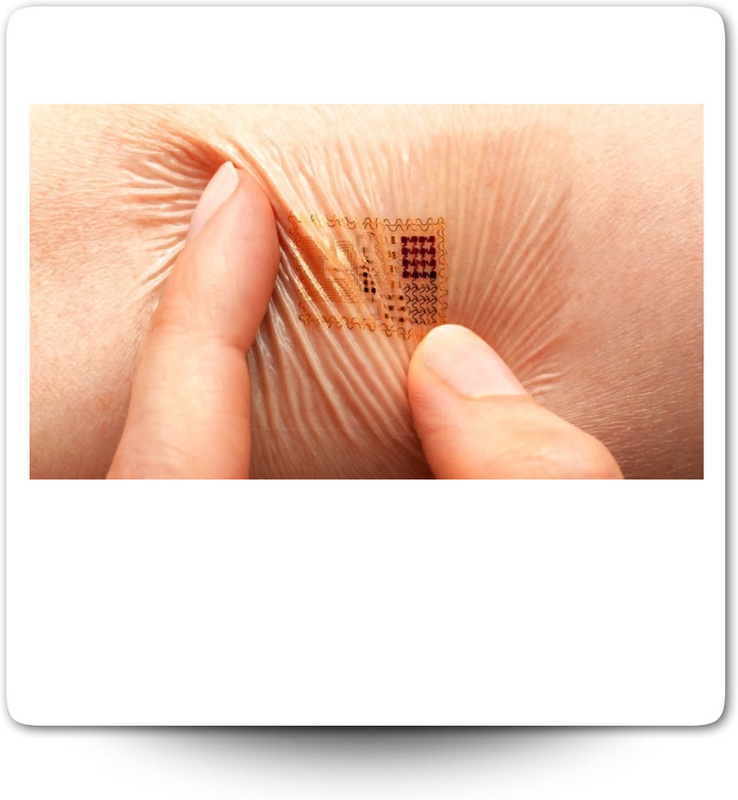

Genevieve Bell, director of Intel’s user experience research, says companies building wearable computers haven’t figured out why people might want them. And she is right: innovation is not about “gear”, it’s about solving a problem. -Philippe. More about Galaxy Gear: http://www.philippemora.net/1/post/2013/09/is-samsungs-galaxy-gear-the-first-truly-smart-watch.html [Thank you MIT Technology Review | By Tom Simonite 09.17.13] Many technology companies are rushing to develop wearable computers without much evidence that people want such devices. Gadget ethnographer: Intel’s Genevieve Bell travels the world to study people’s lives and how technology fits into them. As director of Intel’s interaction and experience research group, anthropologist Genevieve Bell helps the company understand how the chips and other products developed in its labs might fit into the world of humans. Her team of social scientists, designers, and engineers interview and observe people in countries around the globe to understand how they use and think about technology. That work has recently included investigating how people think and feel about technology worn on the body, or wearable computing. Bell is wary of the early examples of wearable computers being readied by companies such as Google (see “Google Wants to Install a Computer on Your Face”), Samsung, and others (see “Smart Watches” and “Samsung’s Galaxy Gear”). She says they won’t be popular until it becomes clear how their technical features can enhance people’s lives. |

head of product in colorado. travel 🚀 work 🌵 food 🍔 rocky mountains, tech and dogs 🐾Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed