|

Tours of duty: the time has come for a new employer-employee compact. You can’t have an agile company if you give employees lifetime contracts—and the best people don’t want one employer for life anyway. But you can build a better compact than “every man for himself.” In fact, some companies are doing so.

[Reproduced from Harvard Business Review] Tours of Duty: The New Employer-Employee Compact [by Reid Hoffman, Ben Casnocha, and Chris Yeh, 06.2013] For most of the 20th century, the compact between employers and employees in the developed world was all about stability. Jobs at big corporations were secure: As long as the company did OK financially and the employee did his or her job, that job wouldn’t go away. And in the white-collar world, careers progressed along an escalator of sorts, offering predictable advancement to employees who followed the rules. Corporations, for their part, enjoyed employee loyalty and low turnover. Then came globalization and the Information Age. Stability gave way to rapid, unpredictable change. Adaptability and entrepreneurship became key to achieving and sustaining success. These changes demolished the traditional employer-employee compact and its accompanying career escalator in the U.S. private sector; they are in varying degrees of disarray elsewhere. We are not the first to point this out or to propose solutions. But none of the new approaches offered so far have really taken hold. Instead of developing a better compact, many—probably most—companies have tried to become more adaptable by minimizing the existing one. Need to cut costs? Lay off employees. Need new skills? Hire different employees. Under this laissez-faire arrangement, employees are encouraged to think of themselves as “free agents,” looking to other companies for opportunities for growth and changing jobs whenever better ones beckon. The result is a winner-take-all economy that may strike top management as fair but generates widespread disillusionment among the rest of the workforce. Even companies that have succeeded using minimalist compacts experience negative fallout, because the compacts encourage turnover and hamper employee productivity. More important, although the lack of job security indirectly creates incentives for employees to become more adaptable and entrepreneurial, the lack of mutual benefit encourages the most adaptable and entrepreneurial to take their talents elsewhere. The company reaps some cost savings but gains little in the way of innovation and adaptability. [more]

1 Comment

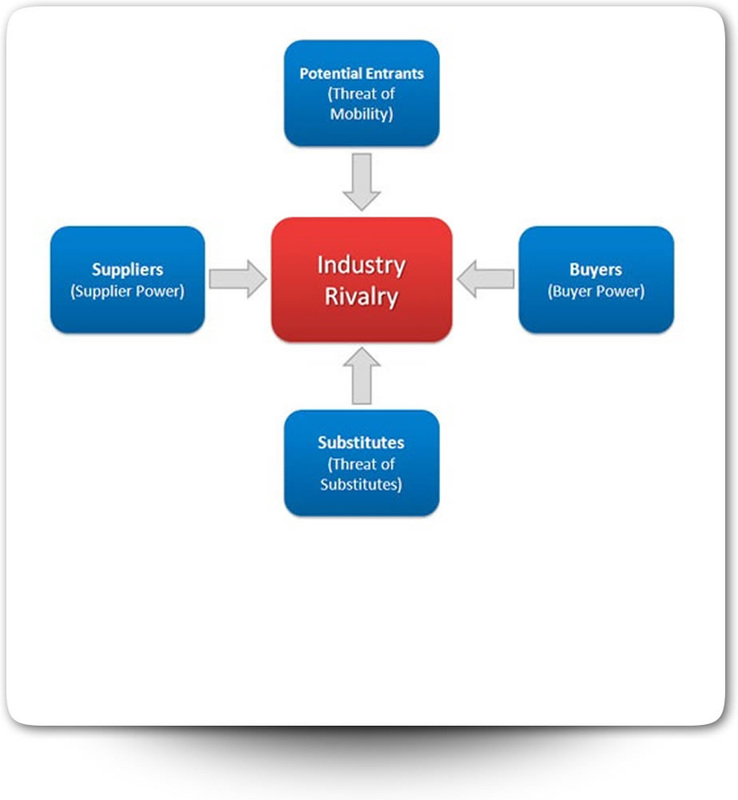

The new dynamics of competition: fascinating read for memorial day that explores an emerging science for modeling strategic moves – and challenges Michael Porter’s five forces model.

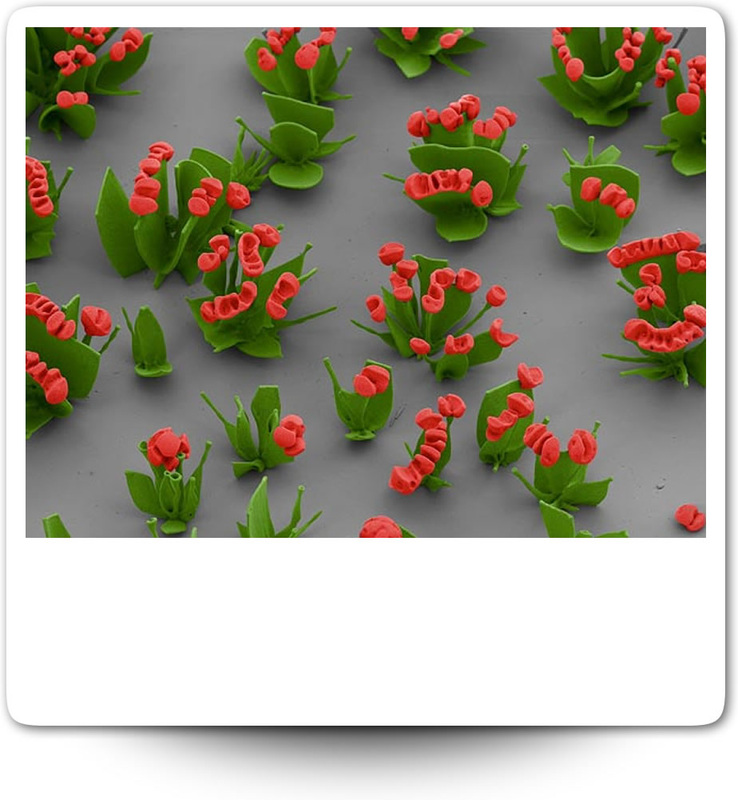

[Reproduced from Harvard Business Review] The New Dynamics of Competition [by Michael D. Ryall / 05.27.13] In his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Peter Drucker made this observation about industries that rely on knowledge-based innovation: “For a long time, there is awareness of an innovation about to happen...Then suddenly there is a near-explosion, followed by a few short years of tremendous excitement, tremendous start-up activity, tremendous publicity....Later comes a ‘shakeout,’ which few survive.” The problem, Drucker argues, is that knowledge-driven innovations are “almost never based on one factor but on the convergence of several different kinds of knowledge.” The initial breakthrough generates a spate of activity, but meaningful progress occurs only after all the pieces are in place. I cannot attest to the scientific merit of Drucker’s claim, but I consider it to be a remarkably accurate description of the field of strategy. In its early days strategy was a loose affair. Content originated either from commonsense approaches such as SWOT analysis or from frameworks like the Boston Consulting Group’s growth-share matrix. In 1979, however, Michael Porter’s five forces model changed the field forever. It masterfully synthesized the practical implications of economic research on industrial organizations from the 1960s and 1970s. Knowledge-based innovation put strategy on the map as a field of study, virtually overnight. Competitive Strategy, Porter’s practitioner-oriented book, became an enormous success. Porter’s ideas generated immediate excitement. They prompted interest from researchers in other fields and the establishment of the Strategic Management Society and the peer-reviewed Strategic Management Journal. A flurry of papers made informally reasoned claims about the causes of persistent performance differences across firms. Theories such as the resource-based view, dynamic capabilities, and transaction-cost economics appeared, and an avalanche of empirical work quickly followed. Another seminal concept, though not as popular with practitioners as Porter’s proved to be, came in 1996, when Harvard Business School’s Adam Brandenburger and Harborne Stuart Jr. proposed “value-based business strategy.” That work has bred an extensive body of literature on strategy by mathematical economists. From that backdrop, a general model of competitive strategy, which I call the value capture model (VCM), has emerged. It uniquely applies the mathematical concept of cooperative game theory to research on business strategy. (“Cooperative” is a misnomer, as the math focuses on competitive dynamics.) As such, the VCM has an explanatory, predictive potential that no other theory of competitive strategy, including Porter’s, can claim. The model is a work in progress, but scholars are starting to use it to explain the dynamics of competition and to identify practical implications for strategic decision making. At the VCM’s core is this axiom: “The value that any party can capture from engaging in transactions with a given set of parties is bounded by the value each of them can add to parties outside the set.” In this article I will explain the axiom and its implications for how we need to think about strategy. Redefining Competition: From Five Forces to One In most industries, a firm, its suppliers, and its customers all have choices about how and with whom they create value. To produce more value, they may change how they engage in transactions with existing suppliers and customers or may switch to other suppliers and customers. Those agents, in turn, have similar alternatives in how they transact with the original firm and with their own suppliers and customers. Nanoflowers grow in tiny garden: Harvard University engineers design beautiful roses, violets and tulips that are smaller than width of a human hair. http://tinyurl.com/ptoz2uw

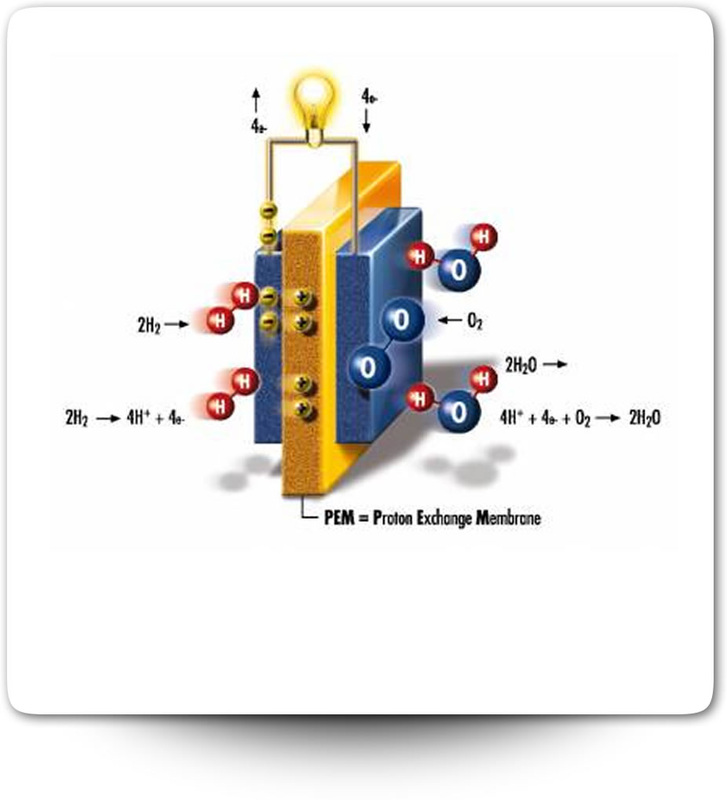

A new type of fuel cell could make CO2 storage cheaper, but it could also prove to be a good way to pump more oil out of the ground. Why It Matters: Carbon capture technology is far too expensive, nearly doubling the cost of power from coal plants.

[Reproduced from MIT Technology Review] Fuel Cells Could Offer Cheap Carbon-Dioxide Storage [By Kevin Bullis] The electrochemical reactions that occur inside fuel cells to generate electricity could provide a cheap way to selectively remove carbon dioxide from the exhaust gases of fossil-fuel power plants. The same reactions could concentrate the carbon dioxide, allowing it to be stored underground. The fuel cell could also be used to generate electricity, providing revenue to offset its cost. Existing approaches to capturing carbon dioxide would nearly double the cost of electricity from a coal-fired power plant. And although using fuel cells instead would still increase the cost of electricity, that increase—based on early tests and calculations—might be one-third or less, says Shailesh Vora, a program manager at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory, which is helping to fund development of the technology with a $2.4 million grant. Researchers have considered using fuel cells for capturing carbon dioxide since at least the early 1990s, but the cells are cheaper now and they last longer, which could make them more practical. Carbon capture technology, aimed at reducing emissions from power plants, might be key to addressing climate change, especially since fossil-fuel power is growing faster than power from low-carbon sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear (see “The Carbon Capture Conundrum,” “Will Carbon Capture Be Ready on Time?” and “The Enduring Technology of Coal”). Technology already exists that could capture carbon dioxide from exhaust gases, but it’s not being used at a large scale because it’s expensive, and because it uses steam that would otherwise be used to generate electricity, cutting a plant’s power production and revenue by about a third. |

head of product in colorado. travel 🚀 work 🌵 food 🍔 rocky mountains, tech and dogs 🐾Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed